The Center for Humans and Nature is an IUCN Urban Alliance member that supports and convenes a global network of leaders and emerging leaders—contemplatives, academics, and activists—who are skilled at bringing a moral lens to the social and ecological challenges we face. In this guest blog, Creative Director and Executive Editor Gavin van Horn demonstrates how storytelling can be used to make urban nature visible and valuable.

“There! There!” Every summer now in Chicago, my son and I tune into the otherworldly buzz of cicadas. They play built-in tymbals on their bodies, marking the season with courtship crescendos that rise and fall through waves of humid air. It would be hard not to hear them in my neighborhood when they reach their symphonic peak. Seeing them is somewhat trickier. But once you put your nose close to a trunk, get eye-level with an exoskeleton still fastened with a pincer-like vice to the underside of a tree limb, you probably won’t be able to stop seeing them. “There! There!” my son shouts, and we marvel at the world abuzz over our heads and the many lives active under our feet, where the next round of cicada nymphs will quietly bide their time until summer returns.

Cicadas are one of many busy urban critters that forcibly remind me that the city is alive. Our creaturely neighbors—adapters, migrants, residents—live and thrive without our permission, sometimes because of us, sometimes in spite of us. Annie Dillard remarks, “Beauty and grace are performed whether or not we will or sense them. The least we can do is try to be there.” How can we “be there” more often, more present to the grace and beauty of the lives that enfold us?

This gets to the heart of the question of visibility, which is a matter of more than what is within eyeshot. For anything—any person, any other creature—to have value, we must first be able to “see” this being as a subject, something that has its own interests, its own claims on our shared place. Visibility is drawing what is otherwise inconspicuous to us into the sphere of our moral attention. This means “seeing” something as a member of our community. Not just background noise but an important voice in our decision-making. Not just background scenery but an interdependent character that shares a story with us.

Making urban nature visible and valuable depends upon storytelling. Writer John Tallmadge captures this understanding well with the following observation: “So much of the quality of our lives depends on relationships, which can’t be weighted, measured, quantified, or even directly observed. We use stories to make them visible” (p.24, in The Way of Natural History). Stories, at their best, crystallize what is most meaningful to us. They orient us and hold up a vision of the world—an ethic for how to live well. They make the unquantifiable visible.

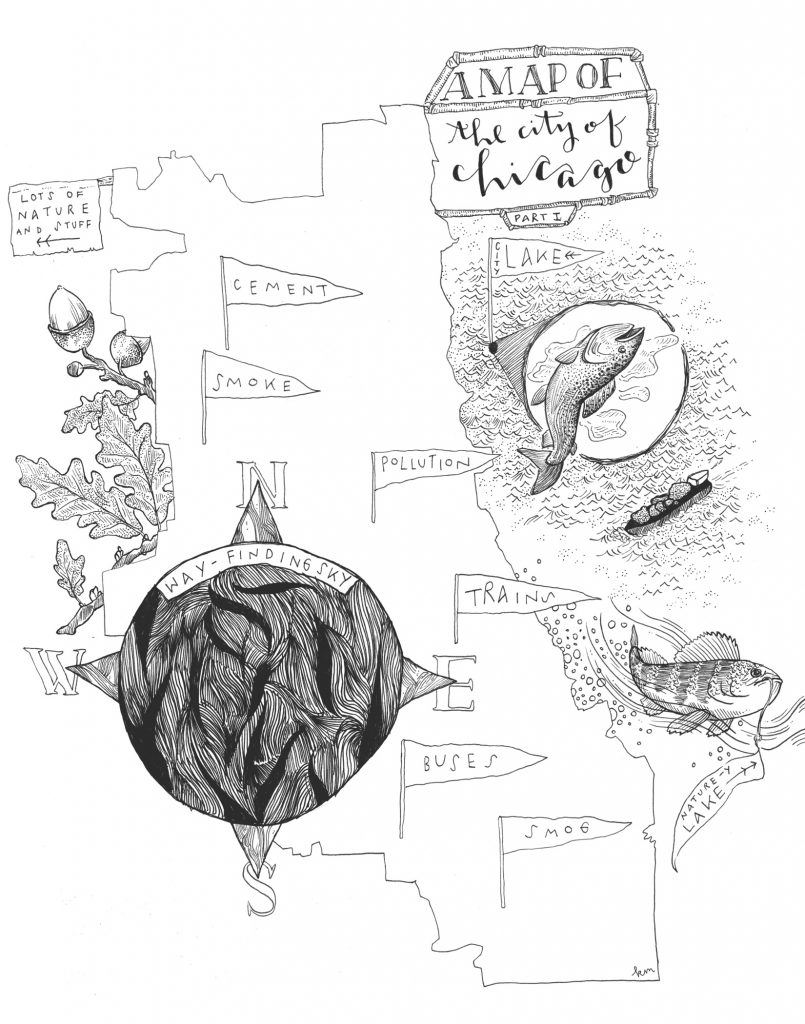

I’d like to share a pair of maps that demonstrate how stories of urban nature can change. When my friend and artist Keara McGraw moved from the suburbs to Chicago, she brought with her a fairly common set of assumptions about the relationship between nature and the city. In one of her illustrations, she captures a number of presuppositions many people have about the city, whether or not they are conscious of this.

As you can see, in the first map the outline of Chicago’s city limits serves as the container for a lot of emptiness, other than the “cement,” “smoke,” “buses,” “trains,” “pollution,” and “smog.” In this depiction, you need to get away from the city to find “lots of nature and stuff.” Without a proper counter-story, I’m afraid this is the mental map of urban nature that many people continue to carry in their minds.

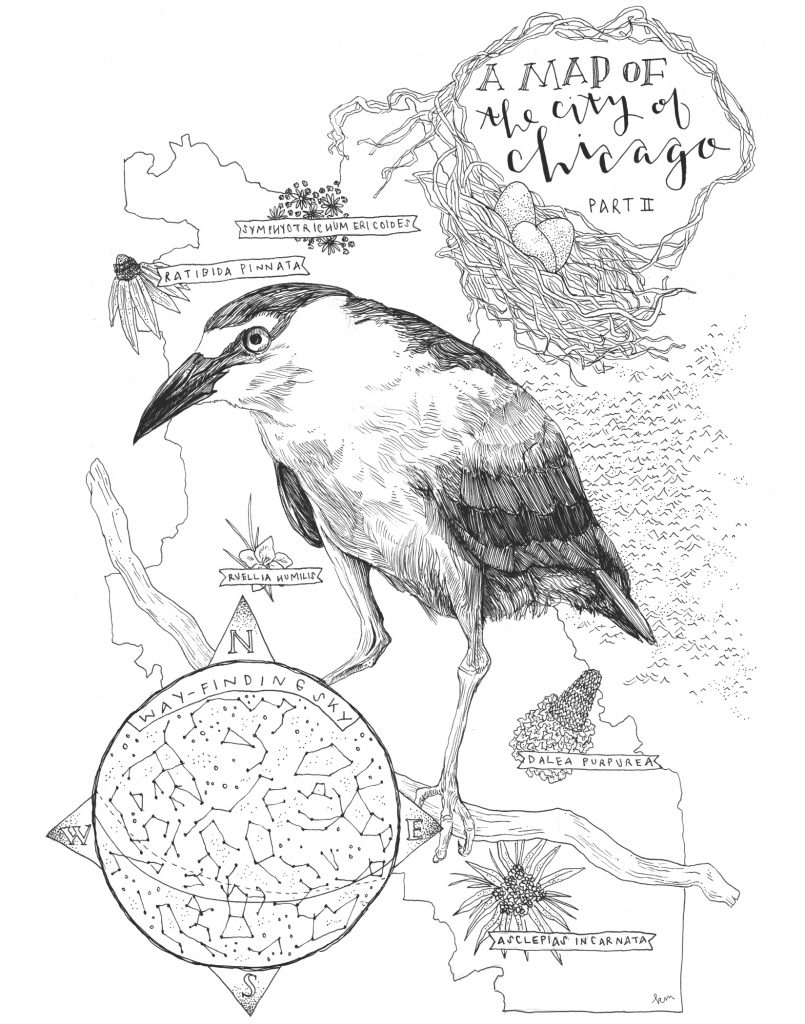

To Keara’s credit, she was open to seeing new things. Perhaps because she’s an artist, she knew how to “be there,” present to the grace and beauty that was once obscured by or absent from her mental map. Once she began learning about the plants and animals that make this city such an exciting, life-affirming habitat for so many, her map changed.

Keara’s new—and by no means final—map reveals a completely different understanding of the city. The central figure in the map may be familiar to those who know their birds. Black-crowned night herons are a state endangered bird in Illinois. They once nested on the far southeast side of Chicago, but now have moved their colonial nesting arrangement to the heart of Chicago, a mere 2.5 miles from downtown. By all accounts, they are thriving. By the hundreds. Their rattling qwawks and croaks fill the urban tree canopy every spring through fall as they hatch and fledge their young. The herons are living reminders that nature can flourish in our cityscapes.

Just like Keara, we all have mental maps. Our stories draw the lines on them, tell us what to expect, what’s possible. Where nature can be found.

In a book I co-edited, City Creatures: Animal Encounters in the Chicago Wilderness, one of our goals was to further a re-storyation of Chicago. We invited our readers to see Chicago, and all urban areas, as multispecies communities. If we perceive our own stories as entangled with the lives of other creatures in the city, we’re more likely to consider their needs, bear witness to their struggles, and take them into account in decision-making, whether that involves planting milkweed for monarch butterflies, designing buildings in a way that discourages bird strikes, or restoring large habitats with other species in mind. Stories may be our most ancient and possibly best means of fostering empathy. They engage our imaginations, creating a space in which we can consider the living realities of others.

A final point: from visibility and value emerges voice. Stories of place that reveal urban areas as lifeworlds—as valuable shared habitat populated by multiple unique and curious subjectivities—can change our mental maps. The show goes on with or without us, whether or not our mental maps are attuned to urban nature or not. But if we do want a more comprehensive story of place, one in which other species are central to our mutual thriving, this requires not only telling stories—making visible—but listening. Voice. I hear the cicadas again. The voices are all around us.

About the Center for Humans and Nature

With a core staff residing in Chicago, the Center for Humans and Nature supports and convenes a global network of leaders and emerging leaders—contemplatives, academics, and activists—who are skilled at bringing a moral lens to the social and ecological challenges we face. Founded in 2003, the Center creates the space—online, in print, and in person—to engage with difficult questions about what our responsibilities are to each other and the rest of the natural world. We do this work in community, in the company of others who bring diverse insights and experiences, to sharpen and spur the critical thinking needed for the future good of both humanity and the planet. The Center doesn’t just think that ideas matter; we believe that the way we understand ourselves and the world is the foundation for achieving our vision for reciprocal, mutual flourishing of humans and nature. Our place in the Chicagoland region significantly informs and inspires this focus. We live and work in an urban area (as do many of our contributors), and we approach cities as more-than-human communities, not separated from nature but connected in every way on a wild continuum. Human economies and communities are dependent upon and embedded within the natural world, subject to real ecological constraints. We believe that insights from contemporary evolutionary biology and ecology allow us to overcome a fragmented vision of reality and see the individual within the context of kinship, community, relationship, and interconnectedness. We promote cultures and communities that integrate science and religion, emotional intuition and rational thought, philosophy and action, biodiversity and human well-being, and conservation and economic plenitude. In line with this vision, we provide a platform for creative, civil, and meaningful exchanges on challenging issues inherent to the conservation, restoration, and rewilding of an urbanizing world.